Okay, let’s straighten a few records, shall we? It is not that we don’t appreciate the fact of a Vice President of a country like Ghana putting himself forward as a cheerleader of digital innovation. We do.

We live on a continent where politicians are usually caricatured as analog dinosaurs who hear “mouse” and only think “rodent”, see “keyboard” and immediately assume “church organ”.

So, especially for those of us whose professional teeth were cut on digital and technology, it is understandable to expect all of us to be jumping up and down at the sight of a Vice President, no less, who stages major speeches at top universities just to big up “digitisation”. Relax, we get the point.

The only challenge a few of us have with Ghana’s current Digitisation Agenda is the consistent disconnect between the big picture and the path to getting us to it. Most of us can agree on how technology can transform this country, from cutting avoidable deaths due to patchy medical records to fighting corruption caused by manual interference with administrative procedures.

Good ideas abound about the use of technology to improve every aspect of life in Ghana. Even if we are not visionaries ourselves, we can, at least, look at South Korea, Singapore and Estonia for quick and easy inspiration.

Most of us can appreciate how clever electronic solutions can reduce teacher absenteeism, optimise irrigation networks, cut ECG’s distribution losses and turn Accra’s nascent commodity exchange into a force that can actually be felt by Anloga-Woe-Kedzi’s tomato farmers. Those facts have never been in dispute.

The opportunities for social improvement using tech have always been obvious but given the chance leaders bungle things.

Procurement Driven Problem Solving

Most adult Ghanaians remember the famous “court computerisation project” initiated in 1998 to stop the antiquated practice of Judges writing down court proceedings in freehand because the country has not been able to implement a basic, modern, courtroom stenographic system.

It turned out that the Ghanaian computer whiz contracted to design and roll out such a system was not exactly Alan Turing, and the Honourable Minister responsible for overseeing implementation couldn’t distinguish between hardware and software.

In the end, the grand $1.3 million (1998 dollars, mind you) project only resulted in a compact disc loaded with a copy of the Ghanaian constitution and a couple of statutes. Till date, having gone through one “e-Justice” program after another, the country’s lawyers still have to rely on manual filings for many court actions.

In short, Ghana’s problem has always been the “HOW”. Much too often, technology-based social change projects initiated by Government agencies are driven more by procurement factors than a genuine understanding of the problem and the proposed solution.

This means that whilst the social and political benefits of solving a particular problem may be clear and would thus influence the decision-making, too little time is invested in careful analysis of the problem and proposed solution by people showing the right amount of professional scepticism.

Very rarely are such people even in the room when the problem is being analysed and the solution architected. Strategies and models for using technology to address social problems in Ghana therefore often lack the requisite rigour that varied professional opinions and debate would lend. The “HOW” is thus all too often not very well laid out.

Lack of Open Scrutiny & Debate

In virtually every serious country, major public sector ICT projects begin with some kind of Government position paper, a request for professional input from technical bodies, and then a rigorous, open, and transparent debate. Thereafter, some kind of expression of interest process opens up and a consortium is eventually selected to execute. Take the process through which the UK Open Banking initiative, for instance, has travelled to date. Or the ongoing effort to develop “quantum networking” in the United States.

In these parts, on the other hand, almost every public ICT project is shrouded in secrecy. Ghana is the only country, as far as I know, that is currently planning to launch a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) in short order without a single public whitepaper laying out for scrutiny even the most basic elements, such as minting, node operator eligibility and consensus protocol design and membership criteria.

In Germany, where Ghana has been lucky to find a contractor to build its CBDC, the central bank has published copiously on its thoughts about how the design should be approached (such as how blockchain settlement can bridge the Euro and crypto domain) and invited lively debate in its rich technology ecosystem. In Ghana, not only has no attempt been made to engage the country’s policy and ICT communities from the ground up, but even basic information about the project is also not available.

There isn’t a single major ICT project driven by the Government that I am aware of that has been shaped by open debate to improve it. And few people can say that they have spent 15 years like I have tracking Ghanaian Government policymaking.

Not the now famously botched mobile money interoperability scheme featuring the mysterious Sibton; the shameful Kelni GVG call traffic monitoring project, which is basically a scam because telco revenue is a “rating” matter not a packet monitoring matter; and certainly not the scandalous Electoral Commission biometric software procurement from Neurotechnology, which independent analysis shows was cost-inflated by almost ten times.

Most of these projects, very much because of poor technical consultation and open discussion of the merits of competing design approaches, underperform over time and fail to transform the lives of citizens.

The above context frames how an activist such as myself, whose misfortune has been to watch so many poorly designed public sector ICT projects absorb scarce resources and still fail to deliver on their promises, should react to digital salvation schemes touted by politicians.

True, some of the Ghana.gov modules seem to have hit their mark. But such seeming successes (and it is early days yet) are exceptions that prove the rule. Ghana.gov benefitted from a deeper degree of involvement by Ghana’s tech community and was executed using a well-tested consortium model. Still, try to get a detailed document on its architecture online and report your findings.

Vice President Bawumia’s latest speech at the prestigious Ashesi University must be appreciated with all the nuances I have raised above. For the sake of brevity, I will focus on only two big picture “digital heaven” ideas he shared and show how deeper technical consultations and livelier, open, debate would have led to far superior design.

Integrating Ghana’s Proprietary Digital Addressing System into Google Maps

This has been a curious policy stance of the Ghanaian administration. Neither Vokakom nor Ghana Post, the two apparent co-developers of the country’s purportedly proprietary digital addressing system (“GhanaPost GPS”), has its own satellite feeds or sources of geospatial data. Their system is entirely dependent on data and infrastructure accessed through Google’s API.

With this GPS data and critical metadata from the same API, GhanaPost GPS assigns labels to polygonal grids using the old “discrete global grids” system that dates all the way back to the 1940s. In fact, Google has its own unique-code generating system for the grid-cells created using its raw data called “Plus Codes” that it has been offering for free for a while now.

Last year, the Navajo nation adopted this free, open-source, solution to provide a complete street-marking and property identification solution that can aid parcel and mail delivery. This year, Nepal did the same.

In simple terms, Google has an API that will give you data in a somewhat rawer state for use in marking landmarks. Ghana paid some contractors to implement this API and affix some labels on it that it calls an “addressing system”. Google also has another free system that can apply the identical labels for free. Countries like Nepal have gone for that, cutting out the unnecessary detour.

Ghana now says it wants to “integrate” its system into Google’s. Hard as I try, I cannot fathom this. Usually, one integrates separate systems that have separate sources of data and structures of functionality.

Google Street View and other digital landmarking services have already databased street and property names in Ghana by the hundreds of thousands. Google has privileged access to GPS and other geospatial data sets. In fact, that is the data source powering Ghana’s so-called “proprietary” system, so the appropriate term for any further collaboration with Google would be “reversion” to norm, not “integration”.

But beyond this confusion, there is a clear problem of poor problem definition and weak solution matching at play here.

The gridding system at the heart of GhanaPost GPS is fixed within certain preset bounds. The grid geocodes cannot therefore cover a physical street address uniquely because a physical street address has fuzzy edges and has not been pre-designed to fit within any preset rectangular grid. Consequently, one physical address can have multiple “digital addresses”. In fact, a place like Hotel Kempinski in Accra’s Ridge area would have many dozens of such “digital addresses” should they be based on geocoding of rectangular or polygonal grids.

In such a circumstance, replacing the GPS coordinates that many apps can capture and transmit with a supposedly unique “digital address” adds no real value as the so called “digital address” is not a unique one-to-one mapping system for street addresses. It is an arbitrary imposition based on selecting one of several dozen options, printing it out on a plaque, and sticking it on a gate. A user could get by using any other referent, such as a geolocation code generated by WhatsApp, for example. With this referent printed on a package, the courier can navigate to within the same approximate location, provided their internet service is fine.

We have in the past publicly urged the government to focus on how to embed generic GPS-based geolocation capacity within Ghana Post’s digital systems for enhanced mail routing based on efficient distribution algorithms. We have pointed out that the digital addressing system, in its current form, is a diversion of resources from what Vokakom and Ghana Post really ought to have spent the millions of dollars voted for the project on. Which is: digital transformation of Ghana Post to be able to better deliver packages to doorsteps all over Ghana.

These public entreaties have fallen on deaf ears. After all, not once in the history of public ICT deployment in this country has open, robust, healthy debate about the merits of competing approaches of deploying technology ever been given a chance.

Turning Ghana’s Identity SmartCard to a e-Passport

Another interesting problem posed by the Veep is how Ghanaians can use their passports and their national ID cards interchangeably. The solution to this conundrum is apparently to have the national Identity SmartCard (Ghana Card) conform to ICAO global standards for e-Passports.

Once again, both the problem and the solution would have benefitted from a lively debate in Ghana’s tech ecosystem. Because had any technologist, who has no conflicts of the procurement type, been asked, they would have raised many basic questions.

The starting point is: how are most countries deploying e-Passports today? Is it by turning their national ID smartcards into standalone e-Passports? The answer is a resounding “NO”. That is not the best practice currently.

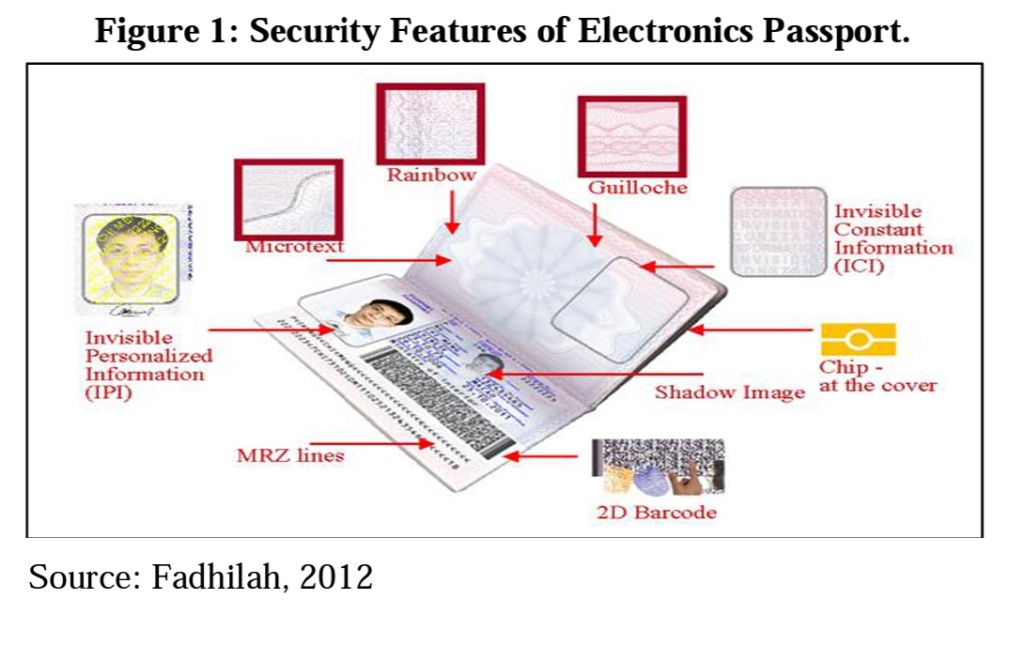

India, to mention just one country, is not turning its Aadhar card into a e-Passport. Instead, it has embedded the ICAO-compliant smart chip (such as a microprocessor or a large-capacity RFID tag) into the cover of the passport itself as the illustration below copied from another author shows. Most countries are using this route.

The reason is simple: a passport is designed to be BOTH machine and human-readable in all its essentials. Furthermore, most e-visas and other electronic travel elements must also have a physical component for a host of reasons including, increasingly, the use of braille for the visually impaired, among others.

To the extent that virtually every country in the world insists on issuing a physical counterpart to its e-visas, a smartcard cannot be a worthy substitute for a physical passport for a long time to come.

The point has been made that a smartcard can be a physical substitute for a passport for travel within an immigration union (such as the Schengen Area) or for citizens returning from overseas. Fine, but such citizens would have used their passports to exit the country and if they are permanent residents or nationals qualifying for the Ghana Card, then they will already have a Ghana Passport or Ghanaian Residence Visa. So, how does adding e-Passport capabilities to the Ghana Card instead of the Ghana Passport become such a priority?

Yes, Half-Baked Solutions Costs Ghana More

A reader may puzzle over the whole importance of this matter. I insist that it is an issue because the weak framing of the problem throws up half-baked solutions and distracts us from asking whether resources being pumped into pursuing e-Passport capabilities for the Ghana Card should instead be spent beefing up the acquisition procedures for both the Ghana Card and the Ghana Passport (which, by the way, is overdue for a security upgrade).

Just as money spent on digital addressing could have been better purposed to address the problem of market distrust due to weak credit referencing, money spent on e-passporting for the Ghana Card could go into tightening the loopholes that are allowing foreigners to grab identity documents meant for citizens left, right and center.

In much the same way that asking someone to stand somewhere and generate a geocode to append to their bank account makes no difference to the bank’s willingness to trust them not to abscond with borrowed funds, so will adding passport biodata to a smartcard so that it can be read by ICAO-compliant terminals do little by itself to improve trust in Ghanaian identity documents at home and abroad.

The solutions looking for problems mindset is becoming pervasive. Not a week goes by without some government agency trying to foist its own definition of an industry problem complete with a procurement-driven packaged solution on some hapless group of citizens or businesses.

Not too long ago, it was the National Identification Authority trying to boost uptake for its expensive “express services” by forcing government workers who have already been enrolled into the Controller General’s biometric database to mandatorily procure a Ghana Card or forfeit their salaries.

The Bank of Ghana too is trying to impose datacenter solutions on banks in the name of cybersecurity. Some of its subsidiaries tried to force eZwich on a reluctant system for years before giving up. There is nothing wrong with state activism in favour of innovation. Where such activism is not subject to rigorous scrutiny and transparency but is largely driven by opaque in-the-shadows interests, as many ICT projects in Ghana often are, then there is cause for alarm.

So, yes, like the next internet addict down the road, I prefer a Vice President going on and on about the power of technology to rescue his nation than one who spends his time amassing rare Lamborghinis. I am only pleading that besides just touting solutions deployed, more time and effort should be expended on opening up the design of these solutions for scrutiny to ensure that they are really up to scratch.

Else, Ghana will merely be celebrating show and pomp, whilst its real problems continue to fester.